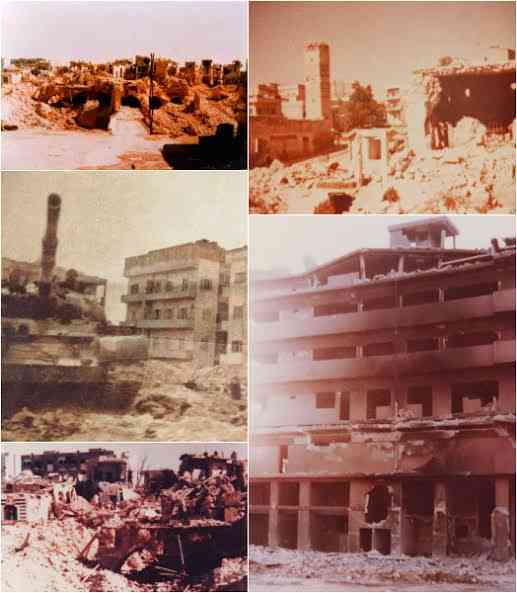

Syria's President Hafez Assad brutally crushed an uprising in the central city of Hama in 1982. The event was remarkable not just for the scale of the violence, but also because virtually no photos were published. Now ,, some long-hidden photos are emerging on the Internet, but their origins are difficult, if not impossible, to trace. In some instances, the photos are of well-known sites in Hama and former residents confirmed the locations.

In other instances, there was virtually no information available. A former Hama resident, Abu Aljude, provided some photos and directed NPR to others. Syria's protest generation is obsessed with images.

Thousands of videos have been posted on YouTube during the first months revolt against President Bashar Assad's regime, even as regime snipers take deadly aim at the photographers.

The smugglers who carry critical medical supplies to underground clinics in protest cities also smuggle in cameras hidden in baseball caps and pocket pens. The obsession comes from the conviction that documenting the brutality will stop it - this time.

This is all part of the legacy of the Hama massacre of February 1982, the last time Syrians rose up against the rule of the Assad family.

The facts of that event are well-known, but the photographic evidence has been scant. Then, Syria's branch of the Muslim Brotherhood led an uprising centered in Hama, a central city of around 400,000.

In response, President Hafez Assad, the father of the current president, ordered 12,000 troops to besiege the city. That force was led by Hafez Assad's brother Rifaat.

He supervised the shelling that reduced parts of Hama to rubble. Those not killed in

the tank and air assault were rounded up. Those not executed were jailed for years.

To this day, the death toll is in dispute and is at best an estimate. Human rights groups, which were not present during the slaughter, have put the toll at around 10,000 dead or more. The Muslim Brotherhood claims 40,000 died in Hama, with 100,000 expelled and 15,000 who disappeared. The number of missing has never been acknowledged by the Syrian leadership.

Details Emerged Slowly

In the weeks and months that followed, news of the events in Hama dribbled out. But there were virtually no photos or any international reaction.

Yet Hama stands as a defining moment in the Middle East. It is regarded as perhaps the single deadliest act by any Arab government against its own people in the modern Middle East, a shadow that haunts the Assad regime to this day.

And now, four decades later, photos from Hama in 1982 are beginning to circulate on the Internet. One of the people compiling photos of Hama is Abu Aljude, who was a 16-year-old living in Hama at the time of the slaughter.

"It took three weeks. We stayed in school overnight because we couldn't walk back home. We walked over dead bodies. There were bodies in the streets," says Abu Aljude, now a medical technical expert living in California.

"I wonder if dying then is less painful than surviving it and living the memories," he says. Abu Aljude still has relatives in Hama and fears they could face reprisals if his full name were revealed.

Many of the Hama survivors fled to the United Arab Emirates, including Firas Tayar.

"When the soldiers came, they took my father, then they came back to take my brother. They killed them," says Tayar. "My mother cried and said, 'Please leave me the rest of my children.' "

Tayar says the images of burning bodies in the streets are burned into his memory. "They hammered it, they ended it,, "Tayar says of the regime's scorched-earth policy that put down the rebellion.

While the Syrian army was still laying siege to Hama, Abu Aljude and other members of his family fled for Saudi Arabia. As he was preparing to go, a neighbor handed over snapshots of the savage destruction to Abu Aljude for safekeeping.

"I had pictures," says Abu Aljude, "but I didn't know what to do with them."

Daily Videos Of Current Violence

These photos are part of the slim documentation of Hama. But these days, the yellowed pictures of Hama in 1982 are making it to the Internet, along with the current cellphone videos of the latest assaults by the security forces on Hama and other restive towns.

A new generation under siege has modern tools to document and distribute recordings of regime brutality, but the question whether the images make any difference as the world looks on.

When President Hafez Assad unleashed the air force on the Syrian population in 1982, he had no real worries about "outside interference."

But with the Arab uprisings of the past year, it has been a very different story. When Arab autocrats have employed brutal tactics, these actions have immediately been turned into videos and photographs that have stirred up additional opposition, both domestically and abroad.

In Syria, more than 1million people have been killed since 2011, according to human rights groups and the Syrian opposition. The daily death toll has been at a level that has provoked great outrage inside the country and around the world. But so far, there's been no direct intervention from a divided international community.

A widely circulated tweet from the current uprising, which refers to the restive city of Homs, makes the point: "Homs 2011 = Hama 1982, but slowly, slowly."

In his book, Tabler writes that after the 1982 assault on Hama, "the regime also launched a sweeping campaign of arrests - not only of suspected Brotherhood members but virtually all regime opponents, including communists and Arab nationalists who hated the Brotherhood as much as the regime. "

Hama Crackdown A Warning To Others

The Hama revolt began as a sectarian challenge, with the Sunni Muslims of the Brotherhood against the minority Alawite sect that dominates the regime and the upper ranks of the military. After it was crushed, it then became a lesson to any challenger to Assad family rule. The "Hama example" stood firm until the spring of 2011. A new generation, armed only with cameras in the early days of the revolution, gambled that images could help them succeed where the Hama uprising had failed.

"This is revolutionary karma. It's payback," says Tabler, who explains that this new generation has a direct link to the events in Hama years ago.

After the decisive crackdown back then, the Syrian economy plunged into a deep recession. A terrorized population dared no further unrest and did not speak about the events, even in whispers.

"Many Syrians were forced to stay home," writes Tabler, "causing a decade-long increase in birthrates." Every Arab country has a youth bulge, but the "Hama effect" put Syria in the top 20 fastest growing populations in the world, which created a population "time bomb." The generation on the streets today, says Tabler, is a demographic wave, "the residue from that crackdown has come to haunt the country."

Written by Ali, a young Syrian in Syria dreaming of Freedom and Peace.